By Alex Kirby

The eagles struck from the side (Image courtesy of John Megahan)

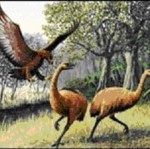

The eagles struck from the side (Image courtesy of John Megahan)One of the largest birds of prey ever recorded, an extinct giant eagle, was once New Zealand's chief predator, DNA evidence from fossil bones indicates.

Research published in the journal PLoS Biology says the bird, Haast's eagle, was big enough to rule its environment.

The eagle increased its weight at a rate unprecedented in other birds and animals after reaching New Zealand.

But it was driven to oblivion about five centuries ago, just 200 years or so after the first humans arrived.

The research is the work of scientists from the universities of Oxford, UK, and Canterbury, New Zealand. It was mainly funded by the UK's Natural Environment Research Council (Nerc).

Additional support came from the Wellcome Trust, the Leverhulme Trust and the Foundation for Research Science and Technology New Zealand.

The researchers, led by Professor Alan Cooper from Oxford's Ancient Biomolecules Centre, extracted DNA from fossil eagle bones dating back about 2,000 years.

Dr Michael Bunce, who carried out the research, said: "When we began the project it was to prove the relationship of the Haast's eagle with the large Australian wedge-tailed eagle.

"But the DNA results were so radical that, at first, we questioned their authenticity."

What they showed was that the New Zealand bird was in fact related to one of the world's smallest eagles - the little eagle from Australia and New Guinea, which typically weighs less than 1kg (two pounds).

Yet the Haast's eagle weighed between 10kg (1st 8lb) and 14kg (2st 3lb) - between 30% and 40% heavier than the largest living bird of prey alive today, the harpy eagle of Latin America, and was approaching the upper weight limit for powered flight.

Dr Bunce said: "Even more striking was how closely related genetically the two species were. We estimate that their common ancestor lived less than a million years ago.

"It means that an eagle arrived in New Zealand and increased in weight by 10 to 15 times over this period, which is very fast in evolutionary terms. Such rapid size change is unprecedented in birds and animals."

Dr Richard Holdaway, a palaeobiologist at the University of Canterbury, said: "The size of available prey and the absence of other predators are, we think, the key factors driving the size increase. The eagles would have been able to feed unhindered on their kill."

Nerc says: "Haast's eagle is the only eagle known to have been the top predator in a major terrestrial ecosystem.

"They hunted moa, the herbivorous, flightless birds of New Zealand [now also extinct], which weighed up to 200kg (31st 7lb).

"With a truncated wingspan of around three metres, for flying under the forest canopy, the eagles struck their prey from the side, tearing into the pelvic flesh and gripping the bone with claws the size of a tiger's paw.

"Once caught, the moa would be killed by a single strike to the head or neck from the eagle's other claw."

The scientists believe the eagle died out within two centuries of human settlement of New Zealand, which happened about 700 years ago.

Forest fires destroyed its habitat and humans exterminated its food supply. There is also some evidence to suggest the eagles were hunted.

Before humans arrived, New Zealand had virtually no terrestrial mammals apart from bats, the only inhabitants were about 250 species of bird. There is no evidence the giant eagles ever attacked people.

Other research in progress involves the DNA from ancient moa droppings, and from soil in former petrel breeding colonies.